Wabakimi | Paddling Through Fire: Part One

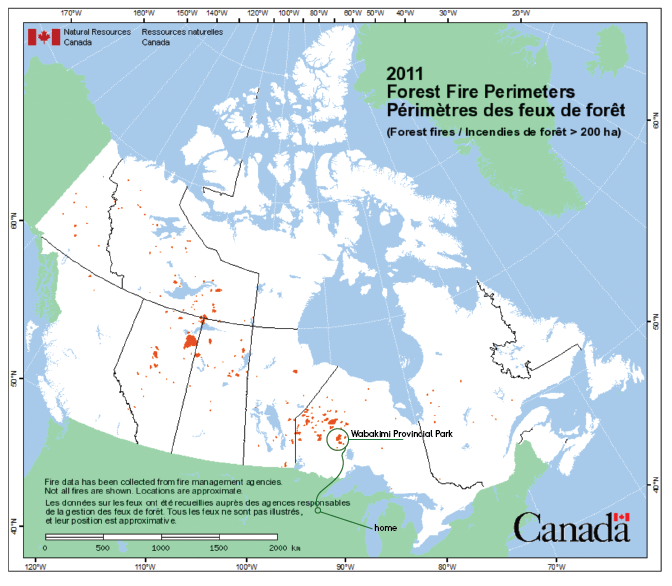

This is a three-part series and true story of a wilderness canoe adventure we took in 2011. It was the summer of wildfires, both in Minnesota and Canada. On a dry, hot day in mid-August, we headed north from our home near Minneapolis. One of the largest fires to date was raging in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness; the Pagami Creek Fire. What began as a lightning strike quickly burned over 92,000 acres. But our destination was well beyond that and north into Canada. A couple days later we took a Beaver float plane into the heart of Wabakimi Provincial Park.

Situated in northwestern Ontario, the boreal forest is with more wildlife than people. In 2011, an average of 250 canoeists paddled the two million acre wilderness each year. During our ten day adventure we only saw one other group. During our journey we experienced a changing landscape, dramatically altered by wildfire. It was a short and steep lesson in the evolving cycle of northern forests. Follow along as we share this short series of our experience in Wabakimi, paddling through fire.

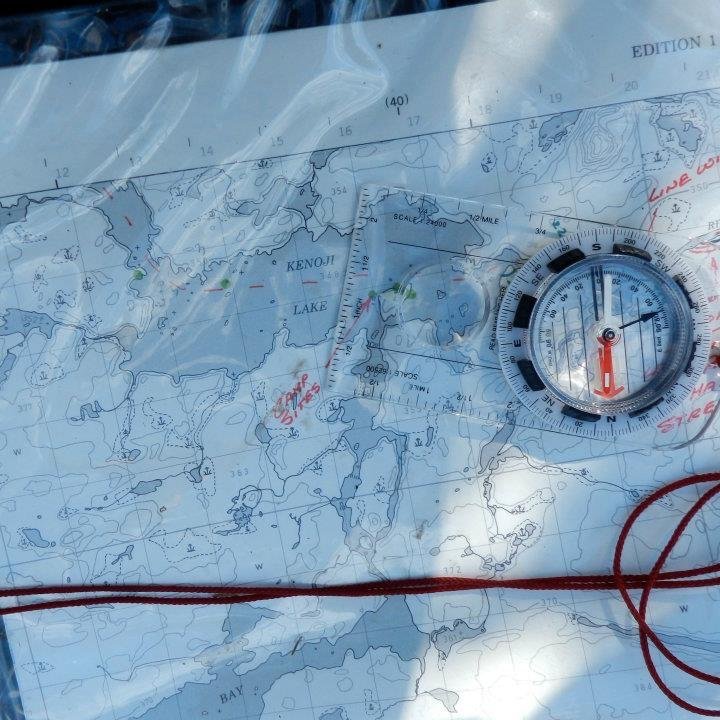

1975 map with notes. Not much had changed.

Palisade Lake. August, 2011. Here begins the tale of our greatest wilderness adventure to date. Our first three days in Wabakimi Provincial Park were so packed, we’re having to break our report up and cover just the first two, here. But you’ve waited long enough, so let’s go!

A Float Plane to the Wilderness

Armstrong Station, Ontario.

As the moonset’s molten colors finally dip behind the treeline, all is dim for just a moment. Then, I have to double-take, as the sky is rekindled by a show of northern lights.

A good start.

It’s 5 A.M. Pam and I pause in our final packing efforts to stand on the deck, relishing the otherworldly lightshow. We’d arrived here at the outfitter’s yesterday afternoon, so we’re well-rested and ready for our 7am flight via float plane.

The Beaver plane will take us over 50 miles into the wilds of Wabakimi, the second largest provincial park in Ontario. For the next 9 days, we expect to have our navigation skills thoroughly tested in its island-studded lakes. We’ve prepared ourselves for a fair share of trail-clearing (if not bushwhacking) along the spartan portages. And we really wanna see a crapload of moose. Please.

Once at the dock, no time is wasted. Gear is quickly loaded aboard the plane and soon the pilot has us soaring high above this unfamiliar country; just us, our two packs, and the canoe. We’ve got an emergency whistle and stuff, also. We’ve tested it. It works.

The sunrise reveals gorgeous lands and innumerable lakes. Below, the green patchwork is intermittently stained with black – burnout areas from recent forest fires.

“You’ve had fires this summer?” we’d asked last night.

“270,000 acres have burned this summer, but they’re just smoldering in a few places now” the outfitter reassured us.

Not any real concern. We’ve learned that paddling through burnouts can be just as fascinating and enjoyable as the ‘pretty’ regions of forest.

And so it’s not an issue that we’re dropped into just such a burnout zone, along a stretch of the Palisade River. With little ceremony and a ‘good luck’, our pilot takes off and we paddle to a nearby campsite to situate our gear and take it all in.

Everything is scorched and desolate. But already, we’re fascinated by our surroundings. We discover what appear to be two primitive fish smokers left by previous campers; one made of pine poles and foil, the other being all flat stones with moss on top. Hardly ‘leaving no trace,’ but somehow it more deeply impresses upon me the ‘differentness’ of the place.

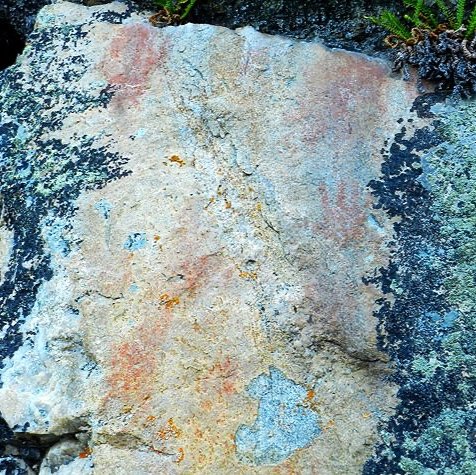

A few hours into our way through the serpentine bends in the river, Pam spots another find: “Pictographs!”

Two dimunitive handprints in red ochre. An arm’s length away, groups of lines, dashes, an “x.” A child learning to count? Or maybe just at play? The mystery captures us.

As we range outside of the burnout area, we already pass by one of the ‘smoldering’ bits we’d been told about. Tired flames on the roots of half-fallen trees. It feels strange to simply paddle by, but here, the Ministry of Natural Resources largely allow fires to burn themselves out unless they threaten human habitations.

Kenoji Lake is the first larger lake we paddle. Far to the south, white smoke from another burnout is visible, but it’s not enough to dampen our spirits. The weather is lovely. Our island campsite is too, although we begin to see some of the Wakakimi-esque traits we’d heard about from others. The site is low to the water on a flat slope of rock. The hearth is a bit smaller than those seen in the BWCA, and needs a little work. There’s a tent pad, but just barely so; it’s small and requires a bit of figuring as to the placement of our tent. All these things we view as positives, though. Things just seem a little closer to pristine, this way. Less trodden down. We cook dinner, send out a “we are here” update from our SPOT satellite messenger, and share a moment with a curious otter swimming by. We pass the evening hours by playing a round of cairn bowling.

Lost Portage Trails and Gathering Smoke

Kenoji Lake to Ogoki River. Today will be a good one. Our map has several annotations about the Ogoki RIver, where most of our day will be spent: “Hazardous stretch”. “Line with care.” Ooo – rapids! (not that we’ll shoot them; we have little whitewater experience. But it’s exciting nonetheless.) Lots of portages – maybe they’ll be really gnarly and we’ll almost get lost! Let’s get started.

A short paddle takes us the rest of the way across Kenoji Lake, to the headwaters of the river. The area is low, with foliage clearly in re-growth from a fire only a few years recent. Just the same, wafts of smoke are seen nearby. Even here, the dry summer’s effects are evident. But it’s just smoldering. Right?

Finding our first portage is indeed a challenge. Driftwood, low water levels and an ocean of underbrush and saplings all work to conceal any telltale path. We’ve noted that some portages here have been identified by surveyor’s tape tied around trees, or by blazes (one modest chop upwards on the trunk, one downwards). So when we do find the portage, I leave the absolutely worst-looking blaze in history, on a dead tree trunk standing by the path. It’s awful-looking, but nobody will miss it now.

Despite the overgrowth, the portage is navigable and free of deadfall. The second one is more challenging; it trails off near the end, leaving us to bushwhack around fallen trees, shrubs and quickmud. But we get there!

As we near more whitewater, our luck in finding portages runs dry.

Wabakimi has rocks, lots of rocks. Did you know that? And boulders, almost everywhere. And every last of them is extremely greasy with a green slime, when wet. If the boulders aren’t hiding just under the surface of the water, ready to shred your canoe like mozzarella, they’re rather a beast to have to clamber over with pack and canoe.

The last 2-3 portages we never find at all. We’re forced to carry the canoe and gear over several boulder fields. The progress is slow – but only so for a while. That ‘smolder’ seems to have grown, and the winds have begun to carry its haze our way. A funny taste begins to sour our mouths. In five minutes, the hazy smoke is directly above us, bathing everything in a strange, acidic light. The smell of smoke is getting stronger.

“I think we need to get out of here,” Pam says, surveying the skies. I’m with her.

We’re able to line the canoe in some spots, but other stretches look do-able to paddle. Sort of. Probably Class 2 rapids… but we’ve never shot anything above Class 1 before. We know, like two things about shooting rapids: you have to scout them first, and also you’ve gotta aim for the ‘v.’ There you go, that’s it. We are so ready.

We pick our course and go for it. The little we know is enough to get us by. We neither dump nor inflict any damage to the boat. Finally there is flatwater again – after spending 5 hours on the 3-mile section of the Ogoki. And thankfully, the wind has changed; smoke is no longer hanging over us.

Enjoying a late lunch break on a campsite, we discover a wrecked fiberglass canoe. And so yes, of course we think, “Wow, that could have been us!” but we decide not to dwell on the thought long.

The Ogoki sort of flows into what is called Oliver Lake, which we follow to a lovely portage. Mosses, blueberry patches and a sun-dappled path make the load seem lighter. After the portage, the Ogoki flows out again, curving northeast towards the massive Whitewater lake. But it’s a lovely, calm stretch and the afternoon is clear. Enjoyment.

In time, we arrive at the confluence of the Berg River with the Ogoki, and here we decide to stay at a campsite. Only, not to enjoy the lovely river views – something else has arrested our attention.

We paddle within view of one rather large plume of smoke, rising high and billowing as we watch.

The Flammagenitus

*That’s* not smoldering.

Looking over the treetops, we can see the fire appears to be quite close (a mere 7 miles away, we’ll later discover.) For the moment, it’s blowing to the south; away from our route. But judging from the map, the burn itself looks to be possibly at a spot along our itinerary, come a few days.

It’s awe-inspiring. Ominous. And who’m I kidding: my sphincter is in major pucker mode. Better watch this thing. Our campsite has a clear vantage point, so we set up the tent and prepare dinner, always with one eye on the smoke plume. It’s continued to mount higher, bearing pyrocumulous characteristics.

“We’re going to have to move if that wind changes direction, though…”

A half-hour after dinner… it changes. The smoke trail now begins blowing to the northwest. Which is to say, a little bit in our direction, but moreso towards where we’ll need to be tomorrow.

Quickly, a gameplan is formed: 3 miles downstream, the river flows into Whitewater Lake. There, at the mouth, is some other outfitter’s fish camp. If the fire and smoke threaten us, from there we could call for help – if there’s a radio. Or, we could use the SPOT messenger to send a distress call for our outfitter. If he’s able to land in all that smoke.

I opt not to count our ‘ifs.’

“How quickly can we break camp here?” Pam asks.

“Half-hour.”

Before long, we’re on the river again. With dusk almost upon us, we figure that by nightfall, we can cover half the 3 miles of river, plus one of the 2 portages along the way. It won’t be safe to paddle after dark, but we’ll be that much closer to relative safety.

The moon is out, and near-full, which helps. And thankfully, the first portage is easy to spot; for once, we’re glad to see that outfitters have left a few boats there. We have to wear our headlamps moving through the brush, but as I carry the canoe, Pam walks ahead and calls out warnings about deadfalls, slippery rocks or outright holes in the pathway.

The portage ends on a sandy beach along the river. It had wound around a set of rapids, and even with the moonlight, it’s unsafe to be on the water any more. Unpacking the bare minimum of gear, we pitch the tent in the sand.

Not at all distant, the plume has taken on a fearsome appearance, the moon illuminating its lofty head, while from underneath, an angry red glow illuminates the bottom half.

It’s just before 10pm. I ask Pam to set her watch alarm for 1am. From that time on, I’ll be prairie-dogging my head out of the tent every 15 minutes… or as often as my anxiety bids me. Watching, smelling.

Continue to Part Two.

Map showing Wabakimi Provincial Park, Ontario and all 2011 wildfires throughout the country. Source: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca

Disclaimer: Information and details provided may have changed since this adventure. Travel is at your own risk. Seasonal and yearly changes in water levels, portage trails and locations are likely. We strongly suggest you contact local outfitters near the park or the Ministry of Natural Resources & Forestry of Canada for current conditions.