Wabakimi | Paddling Through Fire: Part Two

This is a three-part series and the true story of a wilderness canoe adventure we took in 2011. It was the summer of wildfires, both in Minnesota and Canada. On a dry, hot day in mid-August, we headed north from our home near Minneapolis. One of the largest fires to date was raging in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness; the Pagami Creek Fire. What began as a lightning strike quickly burned over 92,000 acres. But our destination was well beyond that and north into Canada. A couple days later we took a Beaver float plane into the heart of Wabakimi Provincial Park.

Situated in northwestern Ontario, the boreal forest is with more wildlife than people. In 2011, an average of 250 canoeists paddled the two million acre wilderness each year. During our ten day adventure we only saw one other group. During our journey we experienced a changing landscape, dramatically altered by wildfire. It was a short and steep lesson in the evolving cycle of northern forests. Follow along as we share this short series of our experience in Wabakimi, paddling through fire.

1976 map with notes. Not much had changed.

Smoke-n-Ash

What time is it?

2 A.M? Thought we’d set the alarm for 1 A.M…? I’ve slept too long without checking the status of the forest fire. I stealthily unzip the tent flap, hoping I won’t awaken Pam. I poke my head out.

The moon casts a dull glow tinged with soot, as dim as a single candle in a darkened hall. Hours ago, the smoke plume seemed crouched; gathering itself up to spring upon us. Now, I see that while the red flames have subsided, its fumes are spread high above us, fanning out across much of my view of the sky.

The beast in mid-pounce? Or are we okay? The air still smells clean…

Laying back down, I don’t know what to do – yet. Better look again every fifteen minutes.

Over several status checks, I can hear a gentle breeze picking up. Then, as I once again peer out: The moon is hidden behind the widening column of smoke. The air smells a bit. I reach for the headlamp. Click. Its shaft of light is a semi-solid dirty grey. Something’s blowing in front of my face, and I blink, refocus my eyes.

The flammagenitus cloud aka pyrocumulous cloud as seen from our temporary camp on the Ogoki River.

Ash. Little bitty bits of ash.

Here’s the part where I know what to do. “Pam… Pam. It’s time to go.”

Not much is said, and thankfully we both just seem to fall into step. Sleeping bags and gear are quickly packed. The tent comes down. And we carry out our only plan: To navigate this unknown river by the light of our headlamps, and search for the portage that will take us past rapids our outfitter had described as “impassible.” From there, a nearby fly-in fish camp will (hopefully) provide shelter, and perhaps a radio with which we can call our outfitter for more information on the blaze. Or perhaps a rescue from it?

Our progress is slow, measured. Despite the three hours’ sleep we’ve had, all our senses are acute. Our eyes scan the shoreline for any hint of a portage. We listen for the sound of faster water ahead. The odor of smoke has now also become that bitter, filmy taste in our mouths again. I find myself having to spit out phlegm every few minutes. Out comes Pam’s bandana. I use the knife to tear it, and we each tie a dampened half over our faces.

Paddle. Drift. Scan the shoreline. Double-take. Nope, no path yet. Paddle. Check for rocks ahead. Now look back, don’t miss anything. Slow down, we may be getting closer. Paddle…

“There it is!” Pam rejoices, after a little over an hour.. “Thank. God.” Mercifully, this portage, like the last, is marked by several canoes and fishing boats used by area outfitters. The sound of the roaring falls close.

“Any other time, I’d hate seeing these boats out here in the woods,” I sigh in relief. “How long is this portage again?”

“A bit over 700 meters.”

It feels risky to double-carry over so long a stretch – about a half-hour each way – with the threat of this fire literally breathing down our necks. Still, hauling my pack and canoe together in the dark, doesn’t rest well with me either. How many deadfalls will we come upon? How clear will the trail be? So we settle for as brisk a pace as we can manage, walking with the packs first. Damped bandanas covering half our faces, we push forward.

The thick forest at night has a beauty about it, but smoke slowly crawls between the trees and seems to be thickening. Good thing the path looks moderately well-traveled.

When we return for the canoe, the light of our headlamps can no longer reach across the river, illuminating only the thick blanket of grey that has moved in. Keep moving. Worst case scenarios in our minds are brushed away for now.

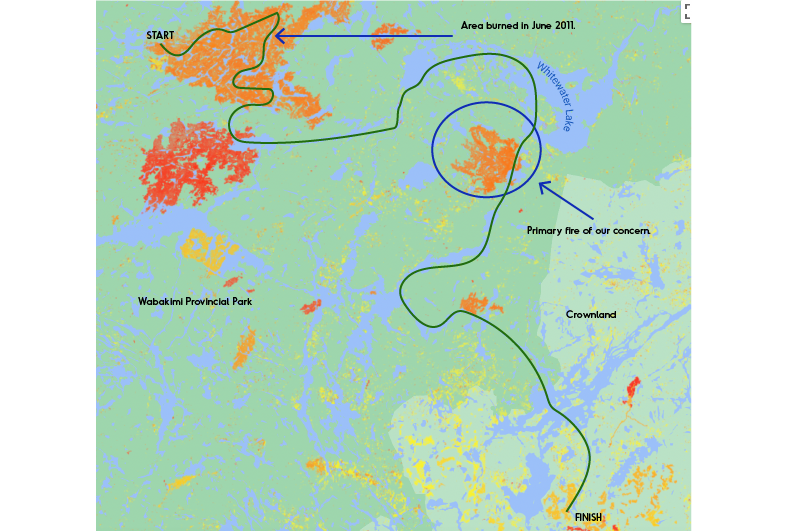

Our 100 mile route in green. Blue circle was wildfire that had us concerned and right in the path of our route. Source: Global Land Analysis & Discovery

Reaching Safety

5 A.M. The end of the portage spills out onto the beach of the fish camp. No boats are to be seen. Taking stock of our surroundings, we see the place is obviously darkened. I approach several cabins, finding them locked and without any sign of staff or guests.

The camp is closed for the season. But we’re feeling desperate for shelter, fresh air (however long it may last) and a chance to plan our next steps in relative safety. I seriously consider using the axe to bust into one of these, though I’d hate to do it… Actually, part of me would love to do it – when does a guy get to smash in a door for any reason? Maybe said relative safety, or even survival, is a good reason. (Note: We would never deface or destroy public or private property.)

No such luck, however. A third cabin has been left unlocked, so there’ll be no axe-play. Inside, the air is fresh. We rest, make some cocoa and, in the interests of keeping our outfitter apprised of our exact location, we send out a ‘we are here’ message on the SPOT. Smoke is evident outside, but we elect to wait until 7 A.M. to assess conditions further.

Today, our itinerary would have us battling ten miles of heavy chop, here on Whitewater Lake – only halfway across its massive horseshoe-like shape. But trying to outrun the ever-thickening smoke? If things worsen, with no radio to use, sending an emergency ‘pick us up’ beacon has to be considered.

Pam finally crashes on a mattress. My nerves are too jangled to allow me sleep, so I kill time and eat an energy bar.

We’re Not Alone

Time passes. Restless, I step outside and walk to the end of a dock, to look back at the treeline we’d just fled from under. Still too dark to see anything telling. But wait… how’d I miss this over here? What appears to be the main lodge sits next to ‘ours,’ and attached to it is a two-way radio antenna! I’m going in.

I flick on the headlamp; step onto the deck. Strange though, how they’d forgotten to store away this outfitting gear: a pair of bear barrels, just sitting out here.

Opening the screen door, I see that the inside door is not only unlocked, but slightly ajar. Seems so weird, how there seem to be

FOUR MEN SHOUTING! WHUH-WHA?! LEAPING TO THEIR FEET! HEADLAMP FLASHING! HEY! BOLTING FOR THE DOOR! I’M SORRY I’M SORRY IT’S OKAY IT’S OKAY!

Bear spray in my face! Shotgun blast to my torso! Swedish-made forester’s hatchet to my Adam’s apple… I’m expecting at least one of these things to befall me, any second now. I’ve gotta allay any suspicions of why I’m intruding, so I say the first thing that comes to mind: “It’s okay! My name is Andy Wright! I come from the United States!”

State my name and country of origin. That’s fantastic. Any hobbies I’d like to share with Mr. Trebek and the studio audience, before we play Jeopardy today? Idiot. Tell them about running half the night to escape the smoke. About needing the radio to learn how much danger you’re all in.

And so I tell them. With a liberal amount of apologies thrown in, for the rude awakening.

The four gentlemen, I learn, are Swiss German paddlers: Urs, Martin, Roland and Daniel. On an itinerary similar to ours, they had camped the night before at the same site as we had, on the Berg-Ogoki confluence. They’d spent a fair share of effort clearing this last portage of deadfalls and overgrowth. By their own admission, they’d been too lazy to pitch a tent, so they’d bedded on the cabin floor for the night. While they’d not seen how large the smoke plume had mushroomed, they had smelled it last night.

“We have satellite phone,” Urs assured me. “We’re going to call… uh, our outfitter in one hour. You can use, too, if you want it.”

An hour? That’s a bit of a wait… although the wind’s shifted slightly and the smoke is less heavy, for the moment. The downtime allows me to report the last few eventful minutes to Pam, who’d been startled from sleep by all the yelling, and immediately thought I was hollering about the fire. She’d been all but ready to send out the S.O.S. call.

The Swiss dudes are now dressed (two of them wearing distinctive buccaneer hats) and brew some coffee water in a large cooking pot over a fire pit as we chat. They are an amiable bunch. I thank them for not macing me, especially when Martin tells me they’d thought I was a bear as I approached.

Urs, the trip leader, contacts his outfitter. She’s aware of the fire (which is on McKinley Lake, southeast of our current position) – but she’s relatively unconcerned. The men are due to be picked up via float plane in a few days, and won’t be going as far as McKinley.

But we will. Our itinerary goes right through McKinley in the next two days!

I don’t have our own outfitter’s phone number. But there is a phone number for the Ministry of Natural Resources tacked to a bulletin board of the cabin. Good enough.

“Where are you headed?” the dispatcher asks me. I tell him we plan to be at an island site for perhaps the next day or so, up on the north side of Whitewater.

“Oh, you should be fine up there,” he says casually. “But yeah, it’s kinda smoky down near McKinley.”

“Kinda smoky. Okay. ‘Kinda’ as in, unsafe? I’ve never paddled through these conditions before, so I guess I’m looking for a professional opinion on whether I should go that way, or not.” And that’s when our connection is lost. Repeated attempts to reach him again, all fail. Ah, well.

Urs and I agree to share each others’ planned whereabouts for the next few nights on the big lake. Should this blaze worsen and people need rescue, knowing this can only help. He and the others will be on the northwest islands of the lake; a few hours outside of our path.

After a brief but friendly farewell, the Swiss contingent soon departs. Tidying and closing up our cabin, we take leave as well. And in good time as the smoke is still advancing. Additionally, inky rainclouds loom to in our path. Best to move while we can.

The chop on the lake is moderate; an effort all morning long, but manageable. The smoke is relentless, however, as it seems to be giving chase. Every time I glance behind us, islands and points we’d passed only ten minutes ago are now swallowed into oblivion.

Intermittent rain falls, serving – we hope – as a wet blanket over the forest fire. Otherwise, if that Lake McKinley is still ablaze when we reach it… we’ll have nowhere to go. The only portages shown on our maps, are the ones hand-drawn for our route.

Pam flawlessly navigates us through the dozens of islands in Whitewater Lake, to our site, nestled among dozens of other islands. Wind direction has changed; the smoke no longer hounds us. Gear is hung out to dry, camp is set up. We discover gardens of moss so plush and deep, a person sinks four inches deep with every footfall. And blueberries! Truly the most lovely-tasting ones I’ve ever had; not large, but imbued with a floral sweetness that intoxicates.

Finally, a respite!

We gorge ourselves on blueberries. Then, on dinner. And on to berries again. The evening is cold and there’s sleep to be had. One more handful of berries.

Exploring the Center of the Universe

Whitewater Lake. Never mind the morning chill – the resplendent sunrise more than makes up for it. Taking advantage of the calm to enjoy the view, we make our way south again. Whitewater Lake being a giant, upside-down “U,” we’re at the curve’s apex, now making our way down the right side. And back into the smoke and the big waters.

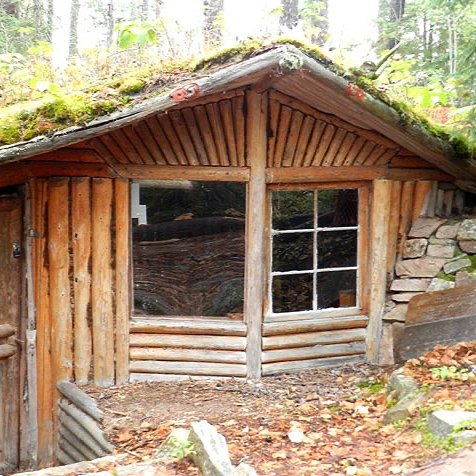

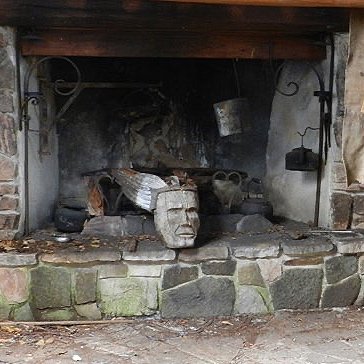

Our mid-day stop: Best Island, the wilderness sanctuary of the late Wendell Beckwith, an eccentric mathematician who lived here for years developing his obscure theories. While their accuracy and validity may be in question, the artistry of his hand-built log dwellings there, are not. An almost hobbit-like architecture and interior design pervades the dwellings, especially his research cabin, dubbed “The Snail.” Thousands of small ‘tree cookies’, or cross-sections, were utilized as floor tiles and roof shingles. The abundance of wood-carved details is a marvel. No wonder he called it the “centre of the universe.” I would’ve made this my world, too, given the chance.

Visitors are allowed to respectfully walk thru, but signs urge us to leave things as we find them. So we take craploads of pictures.

Although the place has fallen into great disrepair, we’re later happy to learn that a grassroots effort is afoot to restore the time-weathered retreat.

Returning to our canoe, my anxiety builds. We’d just spent yesterday fleeing the fumes of the McKinley fire. Now, we face a choice: Either paddle a 2-hour detour to the southern shoreline, where one of our outfitter’s fish camp awaits (with radio and staff present); or… we go for it. Head right into the belly of the beast and attempt to portage through the worst of the scorched acres.

After much debate, we go for it. Bandanas go on again, and it’s off towards McKinley.

It does feel good to be off the white caps of the big lake. Our route meanders through some lovely waterways and portages. Among them, we encounter by far the most lovely portage of the trip. Brilliant green moss carpets the forest; not dead and crunchy moss, but living and vibrant. We’d camp here if we could, it’s so idyllic.

Our joy is short-lived, though. We finally reach the portage leading to McKinley. Or what used to be. Any semblance of a portage path is gone. Blackened trees are littered about everywhere. I can actually hear a few of these dead giants topple as the wind gusts. The ground is smoldering and small tongues of flame are still lingering in several places.

Not good. We don’t feel at all confident. We don’t feel too safe, either. I spit. Grit and bitter smoke in my phlegm. Shoot.

“All right. Let’s turn around.”

Deflated, Pam and I backtrack across the portages towards Whitewater Lake… and the fish camp we’d opted out of earlier. As if to rub our noses in it, the wind and rain kick into overdrive. It’s a 3-hour ‘I told you so.’ Just plain hurtful.

The camp sits astride a sandbar so long, it nearly forms a land bridge to Best Island. Dragging the canoe and our sorry, soaking carcasses across it, we’re exhausted. At least I’m coherent enough to appreciate the humor of my situation as I once again rudely awaken a cabin dweller.

This time though, it’s 5pm and he’s been napping. The guy is indeed the lone employee working this lonely camp; a tall drink of water named John. Our appearance here stymies him; paddlers rarely chance upon this part of Whitewater, he says. Most of them head to the northeast corner, where the Ogoki River outflows once again. Are we doing wildlife and plant studies for the MNR?

No, just a pair of crazy paddlers looking for trouble.

John is terrifically gracious; he puts us up in a cabin, starting a fire in the wood stove. Automatic BFF status for him. Every item of clothing and fabric is hung up to dry, every single one.

Later, in John’s cabin, we use his radio to contact the outfitter. Finally! Now our next steps will be clear.

“Yeah… just head on down through the McKinley portage. I flew over it earlier today at 3000 feet. Should be all right.” he replies, after my description of the condition we’d seen it in.

“We saw it at 30 feet, though. It’d be a long walk over stuff that’s still burning, among trees that are still falling, trying to follow a trail that’s now indiscernible.”

Silence. He’s thinking.

“Well, that, or you could backtrack across Whitewater, up the Ogoki again to the Berg River, and on to the…”

I sort of tune out until he mentions the forecast of high winds, rain and sleet over the next 36 hours. Looking across the room, I can tell by her face that Pam is calculating the wasted mileage. Thirty-some miles.

Everyone can tell that we’re not ready to make a decision. Work out a plan tomorrow. Heck, with the predicted weather, nobody’s likely going anywhere then, either. Better to get a good night’s rest for now.

In a small empty cabin nearby, sleep finds us quickly, but the menace of the fire follows me even into my restless dreams, where a massive grey billow morphs into surreal insectoid faces, ever hovering over me…

Continue to Part Three.

Disclaimer: Information and details provided may have changed since this adventure. Travel is at your own risk. Seasonal and yearly changes in water levels, portage trails and locations are likely. We strongly suggest you contact local outfitters near the park or the Ministry of Natural Resources & Forestry of Canada for current conditions.