Wabakimi | Paddling Through Fire: Part Three

This is a three-part series and true story of a wilderness canoe adventure we took in 2011. It was the summer of wildfires, both in Minnesota and Canada. On a dry, hot day in mid-August, we headed north from our home near Minneapolis. One of the largest fires to date was raging in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness; the Pagami Creek Fire. What began as a lightning strike quickly burned over 92,000 acres. But our destination was well beyond that and north into Canada. A couple days later we took a Beaver float plane into the heart of Wabakimi Provincial Park.

Situated in northwestern Ontario, the boreal forest is with more wildlife than people. In 2011, an average of 250 canoeists paddled the two million acre wilderness each year. During our ten day adventure we only saw one other group. During our journey we experienced a changing landscape, dramatically altered by wildfire. It was a short and steep lesson in the evolving cycle of northern forests. Follow along as we share this short series of our experience in Wabakimi, paddling through fire.

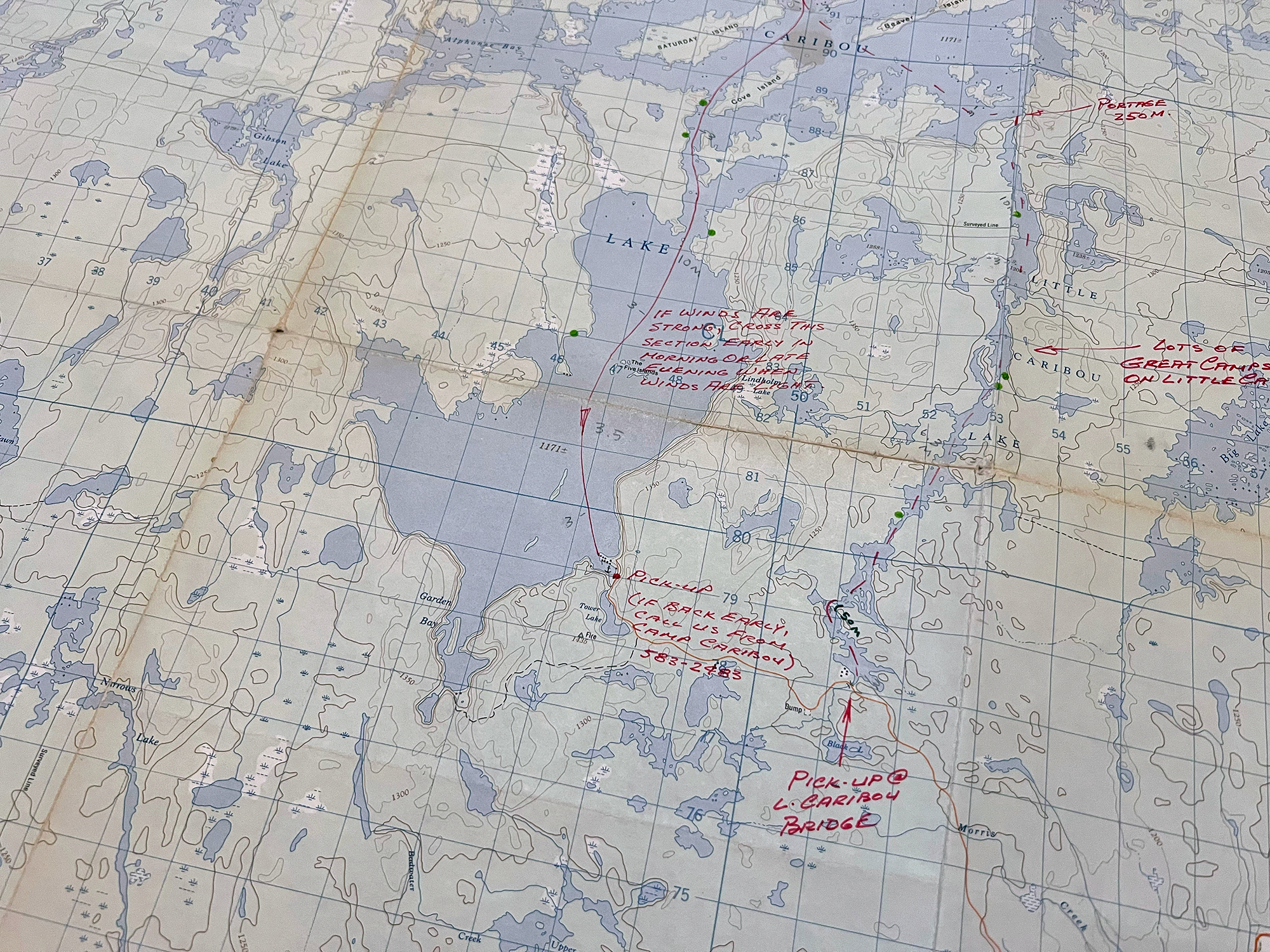

1981 map with notes. Not much had changed.

Where to go Next?

Over a late-morning breakfast, Pam and I review our predicament: Our paddling route has dead-ended where a forest fire had ravaged one (if not several) of our portages. With fallen trees everywhere, flames still licking the ground, and smoke veiling the burnout, we’ve sought the shelter of a fly-in fish camp. Thankfully, the place is owned by our outfitter, whose counsel we sought yesterday via two-way radio.

His advice: Backtrack the 20 miles we’d just paddled on massive Whitewater Lake, taking an alternate route from there. But before making a decision, he’d said, sleep on it. Today’s forecast on the big lake called for mixed rain, sleet and cold winds upwards of 12mph. We might not be going anywhere in weather like this.

But the option would mean dawn-to-dusk paddling for the remainder of our trip, plus two unplanned days backtracking on the big lake. We had jobs and kids waiting back home.

Now, having eaten and dressed, we walk to the staff cabin, where we’ll talk again with the outfitter. Along the beach run hundreds of feet of firehose. A flattened mess, it looks like the dead nightcrawlers one finds washed up on the sidewalk after a rainstorm. Just two days ago, the blaze had come so close, that a crew of firefighters had ‘coptered here to lay them, should they need to spay the row of cabins. We’d even been shown pictures taken from the beach, Smoke and flames, visible just above the treeline. Pam and I are amazed they’d not evacuated everyone. Thankfully, the flames had subsided.

Still, with the specter of fire virtually omnipresent along our route, it’s no wonder we’ve seen no bears, wolves nor moose. Moose—our hopes for sighting them had been so high, after all the stories we’d heard in our research.

Our plan? We dunno. We’re hoping the forecast has changed overnight; that this miniature gale we’re walking through is just momentary. If we must opt to backtrack our route, we’ll need a little more time to muster our energies and let our gear dry out.

“Nobody’s going out on that water today,” notes John, the camp’s lone staffer. Looking out at the whitecaps, he estimates the winds at 12mph already, but the gusts look worse. The outfitter confirms it.

“Yeah, I won’t be flying in this weather. It’s gonna be pretty awful all day. Maybe tomorrow too…” The five-day outlook following that sounds better, but nothing about our next few days sounds good right now—except for the kindness of our hosts, who’ll house us another night. So it seems to be no shocker to them that we’re still unsure of a plan. We need to look at our maps again. Think it over. (Note: We did communicate we’d pay for our accomodations and extra plan shuttle post trip.)

Stuck. Marooned. Beached. Even the fishermen several cabins down are laying low. Our vacation is basically over before it’s halfway through. Bottom line, we just don’t have the two extra days needed to re-trace our itinerary. All that remains is to await our bailout via float plane.

My forehead against the picture window, I blankly stare past the windswept scene in front of me. My perceptions and emotions flag about with the leaves and branches. Outside the door, literally, is a boreal paradise, with hardly a soul around. I couldn’t think of any other place I’d rather be. Yet now, I feel a thousand miles from this wilderness idyll. Everything I’m looking at out there is past tense. I’ve officially hit rock bottom. The Griswold Family car’s been pulled over, Aunt Edna’s corpse is on the roof and we’ve been dragging Dinky the dog behind us for three miles.

We radio again around noon. Conditions have worsened outside; another of the fish camps reported snow today? Do tell—it’s been alternately raining, sleeting, even snowing, every twenty minutes here as well. All day. Snow!

A Way Through

But wait now…what’s this? A ray of hope shines out through the storm front: Our ears perk as a third option is offered up.

“I was thinking…I’ll be flying in your area tomorrow, dropping off another customer to the north of you. I could swing by on the return trip, pick you guys up, and just ‘flip’ you over a few lakes; get you past the burnout area.” He’d charge reasonably for the service, as well. We’ll take it!

Elated. Relieved. Exhausted. With little else to do until tomorrow, we pack our now-dried gear and try to do very little otherwise. Late afternoon. John had earlier invited us to dinner and we’re just killing time now. Outside, the storm rages on, unabated. In the midst of it, a loon sounds its call. Crazy loon, out in weather like this… There it is again, hooting like a lunatic—in fact, a little more like a lunatic and less like a loon. Pam leans towards the window, trying to spot the bird. Suddenly, she straightens up.

“No. Way. You have GOT to be kidding.” she exclaims. Joining her at the window, I hand her the monocle for a closer look.

Two canoes on the sandbar. Four figures standing astride them, embracing and whooping like first-time marathoners at the finish line.

Pam nearly yells it: “I see two pirate hats on their heads!”

I whip on a jacket and run out to help our dear Swiss friends bring their boats ashore. Urs, Roland, Daniel and Martin tell me they’d paddled hard from the far corner of the lake yesterday, eventually camping on a nearby island. They’d laid low today until the afternoon, and hit the worst of the weather coming here.

John graciously puts them up in the cabin next to ours.

Dinner with John feels like home. He makes BLT sandwiches and a fresh salad. Dessert is the only ‘special’ thing we can think of to bring: dried mangoes (woo hoo.) No matter; the talk is great. We ply him with questions about his job, he shares about his Cree-Ojibwe heritage, and his knowledge of that famed hermit neighbor, Wendell Beckwith. John seems to enjoy the company here on this lunar outpost, too. We’re grateful for the kindness.

A Meal Fit for the Swiss

After the meal, Martin (the appointed cook among the Swiss) invites Pam and I over for Dinner #2. “You come, we have spaghett!” he says.

And not just “spaghett”—they’re cooking a whole grocery store in that cabin! It’s amazing: bannock, cured meats, dried fruits, Swiss chocolates, gallon-size Ziplocs full of tea. There’s like, a 5-gallon canister of Nescafé…

Acquaintances quickly meld into friendships. Stories and histories are shared. Especially interesting to me is how Urs, a forester by trade, came to bring his friends across the globe to this relatively little-known wilderness. Don’t they have places like this in Europe? Surely, as a forester, he’d know about them?

“We don’t have this,” he says, spreading his arms wide. “These lakes, these woods, the animals… We have some animals; far fewer though.”

What about way up in northern Scandinavia? Lapland and all?

“Most of it is clear-cut. Here… we saw a black bear the other day. We see beavers… There is so much here.”

John soon joins us all, and the more becomes the merrier. There’s laughter and true fellowship; language isn’t even a barrier.

Looking around the room at this assembly of strangers from three disparate lands, John and I share an observation: We have all truly found the Center of the Universe. And by no surprise, it’s in the Middle of Nowhere—the wilderness—a place where solitude teaches you the value of company; where fleeting glimpses of the little things grant you a better view of the big picture; where even chance encounters with your mortality breathe fresh life into your lungs.

How very true, Urs: There is so much here.

Morning brings with it an early departure. So early, in fact, that we’re whisked away before our Swiss friends awaken. Wait… no time for a group picture? At all? Really? Good thing we all swapped email addresses last night. A pathetic goodbye wave is exchanged from way out on the dock; our farewell as abrupt as that first hello was. ‘Andy and Pam from the United States’ will never forget these guys.

Before we board the float plane, John hands us a parcel wrapped in paper: A gift? We’re extremely touched by his generosity (crap, do we have any more mangoes we can give him?) Here, too, is a friendship just barely begun; our leaving suddenly feels ill-timed. But what can we do?

Soon, we’re soaring over the wide blue lake, then briefly over the green of the boreal forest.

That’s when we see the Black — over 19,000 acres of it. Trees littered everywhere. Boulders, once draped in moss and lichen, now bare and exposed. Smoke still emanating from the singed forest floor. This was the fire that had chased us, plagued us, confounded us over the last four days.

As we fly over McKinley Lake, I spy a crude scattering of field stones — the foundation of what had only days ago been a cabin. The stones are all that’s left of it; they and a small, orphaned dock.

So this was the fire that had chased us, plagued us, confounded us over the last four days. I can’t really find anything to say for several minutes. By then, we’ve bypassed the burnout and are circling over a landing on the long, narrow Lonebreast Bay.

Once again, the dropoff is very quickly executed, and we’re back in the saddle again.

Despite the rather breezy conditions, there’s a lot to be thankful for. Clearer skies and a trip we feel has been rescued; redeemed. Free again. The day goes happily without incident, and come mid-afternoon, a gorgeous site is spotted in a serene inlet of Funger Lake. No wind. No smell of smoke. Several loons are swimming about. This is finally—mercifully—beginning to feel like the trip we’d hoped to have.

As we begin to prep dinner, out comes the gift from John. The papers are unwrapped. Two freshly-thawed steaks from last season’s hunt. Yes, sad to say: these represent what will be our only encounter with moose on the entire trip.

This feels strange, so out-of-place. We would so rather have seen one alive and flourishing! To have captured only its image—not the the thing itself! Yet we’re reminded of what the hunt means to the hunter. It is providing food for those he looks after, those he cares about most: It is for his Family. Unbidden, he has given us this gift, one that we mustn’t squander or take lightly.

The sun sinks, the wind sleeps and the water stills. Calm. Serenity.

Looking ahead, we still have the big waters of Caribou Lake and other adventures awaiting us these last few days. But for now, all the ordeals of the fire are safely behind. We lay prone in the tent, drinking in the silence and basking in a revelation: Best frickin’ steaks we’ve ever had.

Drinking in the Sunshine and Jumping off Cliffs

It felt as though we had started a new chapter in our journey. Gone were the days of wind, fire, then rain. The skies were no longer muddy smudges of yellow and gray, the winds had shifted in our favor. It was like we’d gone from black and white to color. No longer where we paddling through burned or burning stands of trees, dark bark licked from fast moving flame. The world felt healthy and alive.

The channel down into Smoothwater lake was calm, and we marveled at the brilliant black spruce lining the banks like soldiers. After a brief snack along the shore, we paddled into the larger, choppier body of lake, grateful that we would hug a corner that would take us into the pool and drop flowage of quieter waters.

That evening we tucked into a campsite that again, had seen little use in years. The autumn light reflected off the granite boulders that skirted the quiet bay. Warm shafts of yellow and green filtered through the trees as we cooked. Moose steaks were on the grill. John, the manager back at the fish camp had generously given us the meat, taken from a recent family hunt. We savored the nutty, wild steaks - grateful for the gift.

Gifts of the Wilderness

Somewhere around 2am, I popped out of the tent to pee. Shocked, I stood silent, gazing upward.. Moving all around us in peaks and waves was the aurora borialis, the nothern lights. Surging and ebbing into curtains that moved across an endless sky. Stars punctuated the darkess, silent witnesses the riot happening below. If there is magic in the world, this must be it, I thought.

The following days were a study in leisurely, wilderness travel. We stopped on outcroppings coated in soft moss and lichen to have simple lunches. Afternoon breaks included cliff jumping into pools of midnight blue. There was no rush. Winds had shifted, pushing away the smoke while wildfires had been smothered by a few days of persistent rain.

The blue sky and sunshine felt good on our backs as we paddled along and while we had a general destination in mind each night, camping was allowed anywhere. It was usually obvious where a good campings spot might be, generally confirmed by a recent or older fire ring.

The portages here were well travelled and the tread gentle as we passed cascade after cascade. Occasionally the rapids were safe to shoot after a good scouting. One portage had a big scraaaaaaaap across the bark, located just above my head. Upon closer inspection I saw black hairs, the tell-tale sign of a black bear marking its territory.

Sometimes our camp was shared with a shy spruce grouse, but wildlife for the most part was quiet. Knowing that is was nearing the end of the season, many birds had migrated south while other creatures were getting busy for the long winter.

The two packs we carried were getting lighter; we had brought both a waterproof barrel and a soft sided canoe pack. Opting to be light but still comfortable on this trip, we didn’t carry much.

Because there is little traffic in the park, some campsites go unused for years; likely decades. There was little impact aside from the occasional stored fishing boat tucked into the woods.

Our final days took us out of Wabakimi and into bordering the Crownland. The crossing between each area was indiscernible. The woods nor wildlife took notice and only by looking at the map, could we follow the line that marked a border. Since fish camp, we hadn’t seen anyone else, not even the far off hum of a float plane.

The last evening was spent pondering the 100 or so miles we had paddled. The first half had been wild and challenging as we passed through and around wildfires. Chains of lakes were burnt and small pockets of ground fires common. The second half was lush and green with lakes reflected in blue. There is a beauty to both and we were grateful to be experiencing it all.

Later on Little Caribou Lake, Andy chopped wood near the campsite while I filtered some of our last lake water. The night’s were getting cooler, but not cold. We had encountered a landscape in flux, altered by the seasons, wildfire and weather. The land itself constantly reminded us that life is a evolution of hills and valleys, challenges and successes.

The importance of preservation of the historical, cultural and natural resources was not lost on us. Even though we were visitors from another country, the story of the place we were visiting mattered to us. It enriched the memories we created and encouraged us to tread lightly.

People have travelled through the region for ages be it on foot or by canoe. Wabakimi is the ancestral land of the Anishinaabe. The name of the park is an Ojibway name meaning “Whitewater”. The 'drop and pool' characteristic of these waterways features extended sections of river with barely perceptible currents interspersed with close stretches of roaring, often unrunnable rapids. (Source: wabakimi.org) Many have traveled before us and many will again; captured in the beauty and wonder of this incredible wilderness.

RESCOURCES FOR PLANNING YOUR OWN ADVENTURE

The park is within the ancestral lands of the Anishinaabeg people who lived throughout the region. There is evidence of Indigenious activity throughout the park. Please be respectful as you travel.

At 2.3 million acres, Wabakimi is the second largest provincial park in Ontario.

Interior travel and backcountry permits for travel within Wabakimi can be obtained through Ontario Parks. Some of the access to/from the park is on Crown Lands which require their own separate permit here.

Friends of Wabakimi (FOW) is a great resource for planning your canoeing adventure. They provide continued stewardship of the park, mapping and maintaining portage trails while also advocating for the preservation of natural, cultural and historical resources. Maps and guidebooks can be obtained through FOW. Thankfully the maps been updated since our adventure. The topographic maps we used (the only ones available at the time) were from the mid-70’s and our guidebooks were copied from working sketches and notes.

Per FOW, roughly 700 canoeists now visit the park each season. When we visited in 2011, we were told that number was around 300.

Check out the Google map of our 100 mile route that includes campsites and points of interest.

Wabakimi Provincial Park is a remote and wild wilderness area. Should you have an emergency, help may be hours or days away. We recommend this adventure to those with backcountry and wilderness experience. Plan for the conditions you may encounter. Consult local resources such as outfitters located along the edges of the park or the Canadian Ministry of Natural Resources & Forestry.

Safety first! Proficient canoeing skills, ability to read the weather, changing water conditions, navigational know-how and topographic map usage is essential. We strongly suggest you carry a form of satellite communication and be trained in Wilderness First Aid.

Lessons we learned. Understanding the characteristics of wildfires and how to respond if you encounter one is key before traveling into an area. We knew some things, but would have benefited from learning more. At no point were any areas of our route closed to travel and with few traveling through the region so late in the season, we’re not sure how evacs are done.

The MNR however was preparing evacuate the manager of the fish camp. Fire hoses were stationed around camp when we arrived. Safety, is first, our responsibility. Should we have needed a rescue, we understood that personal may not be able travel or fly in poor conditions. At the time we carried a SPOT (satellite communicator). We now carry a Garmin InReach that allows us to send and receive texts and check the weather, allowing us to make more informed decisions.

What we experience on the ground may likely be different than a professional in a distant office will understand. Trust your gut and act accordingly. GIve yourself some buffer days. This would have greatly helped us and allowed us the option to alter our course. Finally, stay calm. Do your best to create a situation that gives you options. Don’t rush helter skelter down a lake or trail - take a minute to pause and let your mind settle. You’ll make better decisions in the process. Finally, while we knew there were fires in Ontario, we had no idea the extent the potential impact they could have on our adventure. We could have inquired better.

Disclaimer: Information and details provided may have changed since this adventure. Travel is at your own risk. Seasonal and yearly changes in water levels, portage trails and locations are likely. We strongly suggest you contact local outfitters near the park or the Ministry of Natural Resources & Forestry of Canada for current conditions.